This post is also available in:

Español

Português

Nowadays, it is widely understood that the term “4:20” refers to a specific time for consuming marijuana, whether alone or in company.

Similarly, most people also associate the date April 20 (4/20) with “International Marijuana Day.”

However, not many people—not even the most seasoned and passionate marijuana enthusiasts—know how or why the number 420 acquired this meaning in cannabis culture.

Some say 420 was a code among U.S. police officers to report marijuana trafficking or consumption. Others claim 4/20 is Adolf Hitler’s birthday. Some even go as far as linking it to a line from Bob Dylan’s song Rainy Day Women No. 12 & 35, since 12 multiplied by 35 equals 420.

Contenido

The Term 420 Comes to Light for the First Time

On December 28, 1990, Steve Bloom, a former reporter for High Times magazine—a publication considered an authority on cannabis culture—was wandering around “The Lot,” a gathering of hippies that formed in the parking lot before every Grateful Dead concert.

It was then that a deadhead approached him and handed him a flyer inviting people to smoke 420 on 4/20 at 4:20 PM.

The translation of the flyer reads roughly as follows:

420 started somewhere in San Rafael, CA, in the late ’70s. Originally, it was the police code for reporting marijuana use in progress, but then local users caught on and began using the expression 420 when referring to marijuana: ‘Let’s go for a 420, buddy!’ After a while, something magical started happening. People began getting high at 4:20 AM or 4:20 PM. Something fantastic occurs when you know your brothers and sisters across the country—and even the planet—are lighting up and smoking with you. Now there’s something even greater than smoking at 4:20. We’re talking about a real-time celebration day for smoking marijuana, the queen of all parties, on April 20. Take a day off from work or school. We’ll meet at 4:20 on 4/20 to celebrate 420 in Marin County, at the sunset point of Bolinas Ridge on Mt. Tamalpais. Just go downtown Mill Valley, look for a stoner, and ask where Bolinas Ridge is. If you make it to Marin, you’ll definitely find it.

HELPFUL TIPS: Be extra careful that nothing goes wrong. Avoid strong winds, no cops, no faulty lighters. Gather with your friends and smoke marijuana.

This is how Steve Bloom originally credited the creators of the flyer for establishing the date as an annual gathering for marijuana smokers.

I brought the flyer back with me and published it in the May 1991 issue of High Times.

Bloom states that for five years, no one questioned this explanation, but the story was only partially correct.

The flyer may have been wrong about the original meaning of the 420 code, but the authors of the message had a bigger mission in mind—they wanted people worldwide to gather once a year to smoke marijuana.

The Story of the “Waldos”

It wasn’t until 1997 that a group of friends who had attended San Rafael High School in the early 1970s came forward and revealed how they had created the concept and coined the term.

The true origin of 420 traces back to Marin County, California, around 1971, when five high school students agreed to meet at 4:20 PM to smoke marijuana, always by a wall next to a statue of scientist Louis Pasteur.

The gathering was originally called “420 Louis,” which was later shortened to just “420.”

The specific meeting time of 4:20 PM was chosen because that was when after-school activities ended.

The group consisted of Steve Capper, Dave Reddix, Jeffrey Noel, Larry Schwartz, and Mark Gravich, who became known as the “Waldos” because their chosen spot was near a wall (“wall” in English) by the statue.

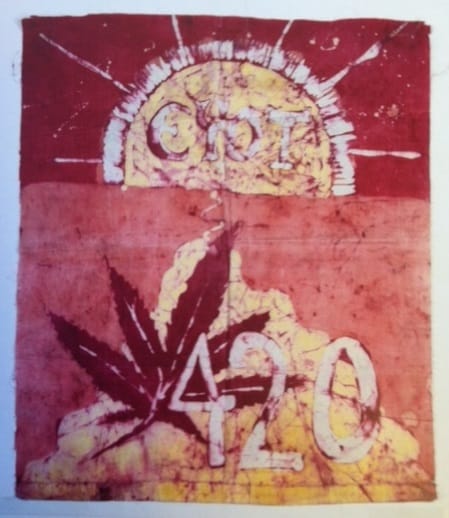

The Waldos had proof—an old flag inscribed with “4:20” and numerous letters referencing 4:20 with postmarks from the early ’70s.

The True Origin of 420 Step by Step

It all began in 1971 when one of the Waldos, Steve Capper, received a “treasure map” from a friend named Bill McNulty, who had gotten it from his brother-in-law Gary Philip Newman, a Coast Guard officer who had been growing marijuana near Point Reyes, where he worked.

Gary was somewhat paranoid about being discovered and arrested since the marijuana plants were on federal property, so he drew a sketch of the location and gave it to his wife’s brother (Bill McNulty) to handle.

Although the Waldos’ initial attempts to find the hidden green treasure were unsuccessful, the group continued meeting periodically to search for the stash.

Steve Capper recalls:

We’d meet at 4:20 PM after school, hop into my old ’66 Chevy Impala, and of course, we’d smoke when we met up, smoke on the way to Point Reyes, and smoke when we got there. We did it week after week. In the end, though, we never found the crop.

But what they did find was a codeword.

I could say ‘420’ to my friends, and they’d immediately know I meant, ‘Do you want to go smoke some?’ or ‘Do you have anything to smoke?’ or just ‘Are you high?’ It was telepathic, depending on how you said it. Our teachers didn’t know what we were talking about. Our parents didn’t know what we were talking about.

Ironically, one of the Waldos was the son of the head of the San Francisco Police Department’s narcotics division (NARC), giving this group of friends special insight into drug search and seizure laws—knowledge that was valuable in the ’70s.

The Grateful Dead Connection

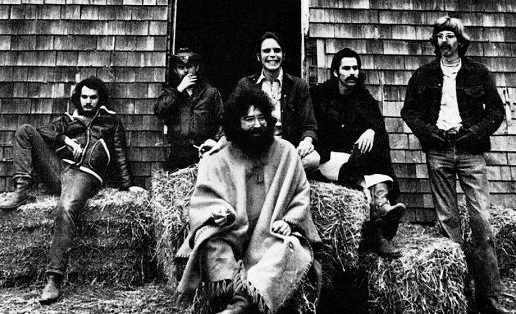

The Waldos had more than just a geographical connection to the Grateful Dead. Mark’s father managed their properties, while Dave’s older brother, Patrick, worked as a roadie for the band and was good friends with bassist Phil Lesh.

The Grateful Dead had a rehearsal space on Front Street in San Rafael, California, where they often practiced.

Steve remembers:

We used to hang out there, listen to them play music, and smoke marijuana while they rehearsed. So, I think the connection likely started there.

The Waldos also had open access to the band’s parties.

We’d go with Mark’s dad—a modern ’60s dad. There was a place called Winterland, and we were always on or behind the stage, running around and using these 420-related phrases. That’s how it started spreading in that community.

Later, as the Grateful Dead toured the world throughout the ’70s and ’80s, performing hundreds of shows a year, the term spread thanks to the loyal group of neo-hippies who followed the band wherever they played.

This is how the flyer ended up in Steve Bloom’s hands, and High Times magazine helped globalize it.

By the mid-’90s, the term had spread enough that Dave and Steve began hearing it in unexpected places (Ohio, Florida, Canada) or seeing it painted on signs and carved into park benches.

No se encontraron productos.

The Return of the Waldos

It was then that the Waldos decided to set the record straight. In 1997, they contacted Steve Bloom at High Times, stating:

The fact is, the police code 420 simply doesn’t exist. Did anyone ever look it up?

Bloom says:

I had to admit—no, I never had.

The magazine’s editor, Steve Hager, then flew to San Rafael, met with the Waldos, examined the evidence, spoke with many people in town, and ultimately concluded they were telling the truth.

Hager confidently states:

There is no record of the use or mention of 420 associated with marijuana before the meaning the Waldos gave it in California in 1971.

Remarkably, all these artifacts are now stored in a secure vault and are available for anyone who wants to review and study them.

Recommended

- 7 Different Plans to Have Fun with Friends Without Going Wrong

- How Michael Jackson Saved Saison Dupont from Disappearing Forever