This post is also available in:

Español

Português

By Javier “Sunshine II” Sánchez

As is traditional in my columns, this Holy Week edition revives the controversial theory that Christ lived in a beer-centric environment and that his deeds and miracles involved this beverage as part of the narrative—not wine, as traditionally claimed.

We’ve all heard the story time and again. In the accounts of Christ’s life, the evangelist John tells us that Jesus (John 2:1-11) meets with his mother and disciples at the Wedding at Cana in Galilee (near Nazareth).

At one point, Mary, noticing the wine had run out, instructs the servants to do whatever Jesus tells them.

Jesus, in turn, orders six stone jars—originally meant for Jewish purification rites—to be filled with water.

Upon inspection, the contents had turned into high-quality wine, allowing the celebration to continue.

For John, this is Jesus’s first miracle. It was, in fact, the first of 39 documented miracles in the canonical gospels.

So far, so good, right? Well, what if I told you it was beer—not wine—that Jesus placed in those jars?

Contenido

The Transformation at the Wedding at Cana

Let’s take this slowly, because I’m likely stirring controversy by suggesting that beer—not wine—was served at the famous Wedding at Cana.

Let’s approach these arguments with an open mind to the possibility of a historical error perpetuated and repeated over centuries.

Several factors must be considered. First, the original Bible was not written in Spanish but in Aramaic, leaving room for variations across centuries of translations by diverse individuals—accumulated changes that may have altered certain details.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone, as even today’s most skilled translators face this challenge. Languages “reflect concepts through symbols that don’t always mean the same thing across regions,” representing interpretations entirely independent of each human group’s reality.

To this day, scholars debate whether Jesus and his father, Joseph, were actually stonemasons, not carpenters—a potential misinterpretation, since the original Biblical texts simply call them “builders.”

The language spoken in the Middle East during Jesus’s time was Aramaic, and some scripture scholars argue these texts may have referred to beer.

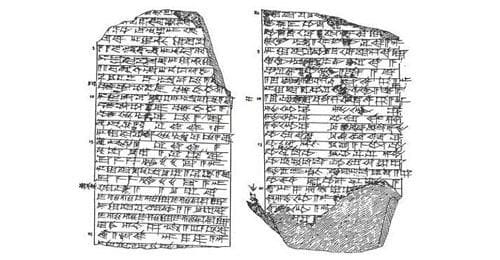

A literal Aramaic translation states Jesus turned water into a “strong drink,” but never specifies wine. That interpretation was coined by the Greeks—the Bible’s first translators—who called it wine [i], as it was their traditional “strong drink.”

Beer—which Greeks associated with northern “savages”—was deemed unworthy of a leader like Jesus.

Moreover, these translations were made long after Christ’s contemporaries had died, leaving no one to correct the “mistake.”

Once “beer” was replaced with “wine” in one translation, subsequent versions repeated it.

Additionally, an early English Bible translation mentions not just “stone jars” but a “line of ale vats.”

Given that “Ale” in Old Germanic refers to an ancient type of beer, things get more interesting, don’t they? [ii]

Let me stoke the fire further: In Jesus’s time, the main crops and trade goods in the Holy Land were grains (barley and wheat), alongside olives, date palms, and fig trees—with grapevines being the least cultivated.

Grapes were rare, introduced to the region just decades before Christ’s birth by the Romans, who were heavily influenced by Greek culture.

It’s logical to assume that when Aramaic texts describe Jesus sharing a “strong drink” from “lines of ale vats,” they meant beer—not wine.

The Last Supper

It’s worth noting that Egypt’s primary export beverage to the Mediterranean region during Jesus’s era was beer. No evidence suggests they exported wine [iii].

We must also consider that millennia before Christ, the region’s traditional “strong drink” was beer, as evidenced by the famous Hymn to Ninkasi [iv] from the Sumerians—humanity’s first recorded civilization—which describes a beer recipe dating back 6,000 years (the oldest written recipe in history).

This originated in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), from where, as Jesuit priest Ronald Murphy (Georgetown University’s German Department chair) notes [v], the recipe spread over centuries to regions now known as Armenia, Georgia, Russia, Israel, and beyond.

Another point: Beer was the drink of the common people. The masses celebrated with beer.

The Wedding at Cana wasn’t for Greek or Roman aristocrats but for ordinary folk—otherwise, Jesus, his mother, and friends wouldn’t have been invited. Thus, it’s logical to deduce the beverage served was beer, not wine.

In Jesus’s time, wine wasn’t an “aspirational” drink for the masses to feel “high-class.” On the contrary, it symbolized Roman oppression—a marker of imperial dominance in the Holy Land. Why would a working-class wedding serve wine?

Beer was plentiful for the plebeians (and Jesus was “of the plebs”), while wine was reserved for elites.

The Bible’s original translators weren’t plebeians but educated Greek scholars who, in stating Jesus offered his friends the finest “strong drink,” assumed it was wine—conveniently aligning with their interests.

We know Jesus didn’t get along with the Romans—quite the opposite. No account shows him breaking bread or sharing wine with Roman rulers or the wealthy, who alone had access to wine.

Historical Context

Often, we envision Jesus outside his true socio-economic context: persecution, repression, violent social struggles, political and religious conflicts, betrayals, murders, disappearances, rape, economic interests, deprivation, hunger, and poverty.

We picture a handsome, bearded man stoically walking Galilee’s shores in pristine robes, surrounded by smiling fans—or hosting the Last Supper in a clean, well-lit hall.

The religious symbol overshadows his harsh reality. Jesus was of the plebs… he ate and drank what the plebs did.

Of course, this theory about God’s son’s first miracle doesn’t diminish his divinity. Turning water into beer is just as miraculous as turning it into wine, no?

What Was Served at the Last Supper?

Now, let’s stretch our imagination further: If they drank beer at Cana, what about the Last Supper? Was Christ’s blood beer instead of wine?

To close, another thought: Know what explorers and armies carried as a staple? You guessed it—beer[vi], as it didn’t spoil like water, bread, meat, or vegetables.

So… was Noah’s Ark stocked with jars upon jars of beer?

The water-to-wine debate isn’t new. It’s been discussed worldwide for years. Archaeological discoveries continue clarifying our past, revealing details hidden or misrepresented for centuries.

We better understand the figures and events shaping our civilization, customs, and religions.

We’ve learned to embrace possibilities—accepting them as fact when science confirms their validity.

Wine or beer? Ultimately, it’s the least important detail. Catholic faith transcends form, anchoring itself in the essence of belief.

No se encontraron productos.

Bibliography

[i] Oxford University Press. Gospel translations by Jesuit priest Ronald Murphy.

[ii] “Alus” in Lithuanian (Last Baltic country to Christianize), “ölu” in Estonian, “Olut” in Finnish, “öl” in Swedish, “ol” in Danish, “Ale” in English.

[iii] History of Humanity Collection. Arlanza Ediciones. Barcelona

[iv] “The goddess born of fresh, bubbling waters who fills the mouth and gladdens the heart.” http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ninkasi

[v] http://explore.georgetown.edu/people/murphyg/?PageTemplateID=128

[vi] History of Humanity Collection. Arlanza Ediciones. Barcelona

Recommended

- Absinthe: Origins and History of the “Green Fairy” That Intoxicated the Belle Époque

- Michelada: Origins and History of Mexico’s Most Famous Beer Cocktail