This post is also available in:

Español

Português

The history of Chilean pisco is not easy to tell. Many original documents from the 16th and 17th centuries were lost in the frequent natural disasters that have struck the country.

The city of La Serena alone, key in the evolution of this spirit, was burned and looted twice during that period. Yet, its story can still be reconstructed.

It is the quintessential local beverage, with origins dating back to the era of Spanish colonization.

Few know about its beginnings, which speak to how its production contributed to the development of the local economy—making it one of the most influential industries in the region to this day.

Contenido

Origins of Chilean Pisco

Chilean pisco is a fine grape brandy, the result of a centuries-old winemaking tradition that began with the settlement of Spanish conquerors in 1541.

As a deeply Catholic nation, Spain brought religion to the territories of the Americas, along with the rite of the Eucharist, which requires bread and wine.

By 1549, in the recently reestablished La Serena—originally founded in 1544 and destroyed a few years later by indigenous people—the first vines for wine production were planted.

According to the French naturalist Claude Gay in his monumental work Historia Física y Política de Chile (1858), the first grapes from La Serena were harvested in 1551.

The dry climate and high sunlight ripened the grapes with a high sugar concentration, producing a sweet, liquor-like wine with high alcohol content.

In his monograph El origen, producción y comercio del pisco chileno, 1546-1931 (2005), historian Hernán Cortés highlights:

By 1558, the valleys of Copiapó, Elqui, and Limarí had the highest concentration of land and indigenous labor dedicated to vineyard cultivation and wine production in the entire country.

Distillation as a Necessity

The sweet character of the wine made it difficult to transport over long distances. Winemakers began distilling part of their production to make brandy, which was far more stable and useful for fortifying weaker wines, improving their flavor.

Gradually, this brandy gained fame for its quality. With its seductive aroma, it accompanied the long days of miners and laborers, as well as colonial gatherings in the few urban centers of the time.

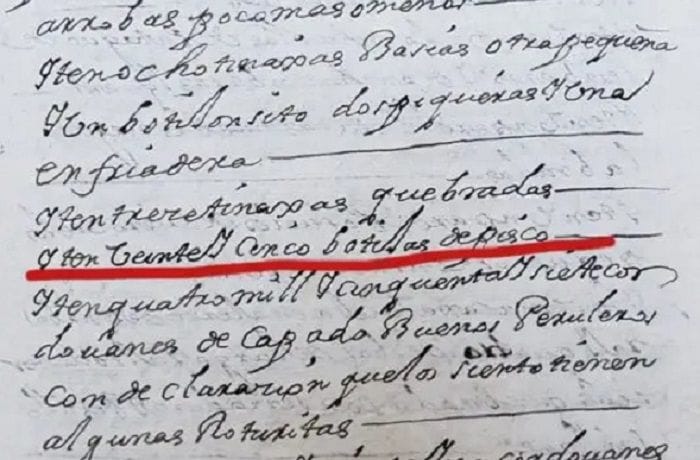

Various historical documents attest to this brandy and its importance to the community.

A decree from the Cabildo of La Serena, dated November 23, 1678, set prices for essential goods; alongside bread, wine, and soap, it established the price of “a quart of brandy at four reales.”

The distilled product found a ready market among mine workers and gold prospectors, as well as in administrative centers, which by the late 16th and early 17th centuries generated growing demand.

First, it was the local mines of Andacollo and Brillador; then Santiago, the capital of the governorship, and the south of the country; later, the silver mines of Potosí and Huancavelica in the Peruvian viceroyalty.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the region maintained a steady exchange of goods with the rest of Chile and the viceroyalty.

From the port of Coquimbo, brandy, wheat, goat leather, tallow, copper, and oil were exported.

In those days, the brandy from Norte Chico was transported by mule in goat leather bags. Ceramic jars, called pisquitos or pisquillos, were also used.

How and When Did This Brandy Come to Be Called Pisco?

The answer is unclear. The most recent study, from 2020, found references to its production in 1717—16 years earlier than the previously accepted date of 1733—at the former estate of Alhué, now in the Metropolitan Region, nearly 500 kilometers south of the Elqui Valley, traditionally considered its birthplace.

Academic Cristián Cofré, responsible for the discovery, states:

In 1717, an inventory of assets was conducted following the death of Bartolomé Pérez de Valenzuela, a landowner in Alhué, to appraise and divide them among his heirs. Among the many materials, products, and constructions on the estate, 25 jars of pisco were found in the winery.

The jars were essential for storing and transporting the distilled spirit to local and foreign markets.

In this case, these jars contained pisco, which was mentioned again in 1718 during an appraisal.

Both documents can be viewed at the National Historical Archive, in the Santiago notaries’ records.

What is certain is that mid-18th-century documents—such as a 1748 will—record the possession of “jars of pisco” among the belongings of valley residents.

By this name, Chilean colonial society began to designate a brandy derived from special grape varieties and grape must, distinct from the distilled spirits produced from the Aconcagua Valley southward, which were made from wine lees and grape pomace.

Chilean Pisco Modernizes

The 19th century dawns. In 1818, Chile achieves its definitive independence from Spain. The new republic embraces modernity. Many artisanal industries begin taking steps toward industrialization.

In 1819, patents for the manufacture of stills in Chile were approved, many of which would be used for distilling pisco. Until then, most of these devices had to be imported.

From the 1850s onward, new technologies were brought from Europe: grape varieties better suited to pisco production, vineyard management systems, and fermentation processes. At the same time, copper stills were introduced, marking the end of the artisanal production phase.

Varieties of Chilean Pisco

In 1861, in the city of Vicuña in the Elqui Valley, local producer Juan de Dios Pérez Arce marketed his brandy under the label “Pisco Italia,” priced at six pesos per jar.

Old family productions gradually gave way to increasingly sophisticated operations. Pisco producers built specialized facilities for distilleries, cellars, and warehouses. In 1873, a milestone event occurred for the future of the Chilean pisco industry.

A decree on November 12 of that year established an official registry for pisco producers’ trademarks, regulations, and emblems—the oldest legal standard referring to pisco in the world.

International exhibitions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries served as the first global showcases for Chilean pisco, which quickly accumulated medals, awards, and accolades: Liverpool (1886), Paris (1889), Buffalo (1901), Quito (1909), Buenos Aires (1910), among others.

The most awarded brands were Tres Cruces, Luis Hernández, and Álvarez. Thus, Chile became the first country to introduce pisco to the world.

Denomination of Origin (DO) for Chilean Pisco

By the 20th century, pisco’s fame, earned over centuries and confirmed by numerous international awards, was firmly established, upheld by traditional families of Norte Chico.

But challenges arose. In March 1931, Chile was mired in a deep economic crisis due to the Great Depression that began in the U.S. in 1929.

In this context, a group of the most renowned pisco distillers met in the town of La Unión in the Elqui Valley to agree on establishing an office to regulate regional pisco, ensuring its circulation with a distinctive label or seal.

On May 15, 1931, a decree defined:

The name Pisco is exclusively reserved for brandies derived from the distillation of grape must, produced within the stipulated regions.

In the 1970s and 1980s, pisco companies enjoyed prosperity. On August 13, 2003, the Association of Pisco Producers was founded, now recognized as a trade association.

This entity assumed sector representation and endures to this day. Its objectives, as defined in its statutes, are:

To promote the sustainable development of pisco production; to foster technological advancement in the pisco industry; to jointly address and resolve scientific, technological, and administrative challenges affecting pisco production and industry; to encourage and support research and technological innovation in the pisco sector.

On May 14, 2009, Decree No. 36 was signed, establishing National Pisco Day, to be celebrated every May 15 in commemoration of the date its Denomination of Origin was established.

References

- Gay, C. (1858). Historia física y política de Chile. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta del Ferrocarril.

- Cortés, H. (2005). El origen, producción y comercio del pisco chileno, 1546-1931. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria.

- National Historical Archive of Chile. (n.d.). Santiago Notaries’ Records. Inventory documents of Bartolomé Pérez de Valenzuela’s estate (1717) and appraisal of pisco jars (1718).

- Cofré, C. (2020). “New Findings on the Origin of Chilean Pisco.” Chilean Journal of Rural History, 18(1), 113–130.

- Lacoste, P. (2010). Historia de la vitivinicultura en el Norte Chico de Chile. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

No se encontraron productos.

Recommended

- IBD Launches Its New General Certificate in Distillation in Spanish

- Causes and Effects of Oxidation in Beer: Everything You Need to Know