This post is also available in:

Español

Português

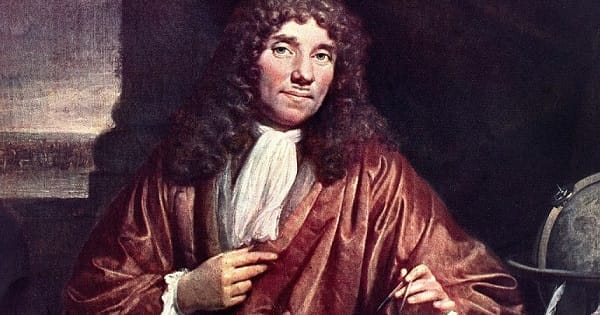

Science had just emerged as a profession, yet it was a self-taught textile merchant who became one of the greatest scientific celebrities in all of Europe.

This is Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch merchant who, in the late 17th century, discovered microscopic life.

Without a university education, Leeuwenhoek became the first human to observe single-celled organisms, bacteria, red blood cells, and sperm using his homemade microscopes and an insatiable curiosity as his only tools.

Contenido

The Scientific Revolution of the Microscope

Amid the scientific revolution, the microscope was the fashionable technological toy among high society, fascinated by the enlarged objects Robert Hooke depicted in his book Micrographia.

When Leeuwenhoek (October 24, 1632 – August 26, 1723) peered through these devices at the fabrics he sold, he discovered his true passion and devoted himself to crafting and polishing lenses.

He perfected his art to such an extent that he achieved magnifications of up to 300x. He built single-lens microscopes, embedded in a brass plate, which he brought close to his eye like a peephole.

This would have ruined anyone’s eyesight, but it allowed Leeuwenhoek to see far beyond what Hooke could, who worked with multi-lens microscopes, similar to those used today but still very primitive.

Leeuwenhoek spent nights peering through that peephole, which opened a window to an unseen world. He examined under the microscope anything that caught his attention.

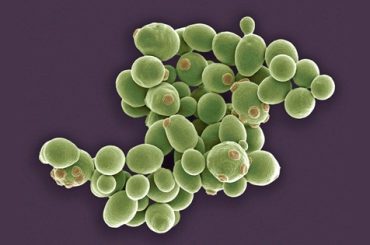

He collected a piece of rotten bread and observed mold fungi; he focused on the tartar of his teeth and saw bacteria; he thought of his blood and discovered red blood cells; one day, he decided to examine his own semen, becoming the first man to see a sperm cell wagging its tail.

This was utterly astonishing at a time when it was believed that semen contained miniature babies or that fleas emerged from grains of sand.

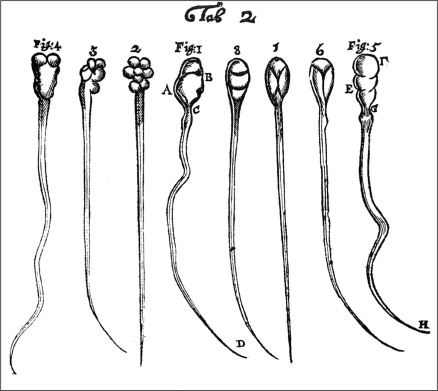

He described the sperm of mollusks, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals, reaching the “novel conclusion” that fertilization occurred when sperm penetrated the egg, demonstrating that sperm were produced in the testes and gained mobility in the epididymis.

Leeuwenhoek took the first step in dismantling the theory of spontaneous generation, but it would take over a hundred years before microscopes superior to his were built, allowing other scientists to continue his work.

He sent his findings by letter to the greatest scientific minds of the time, gathered at the Royal Society of London.

Although Leeuwenhoek knew neither Latin, the language of scientists, nor English, this correspondence in Dutch lasted 50 years, until his death.

Even so, with skill, diligence, boundless curiosity, and an open mind free from the scientific dogma of his day, Leeuwenhoek successfully made some of the most important discoveries in the history of biology: bacteria, blood cells, sperm cells, nematodes, microscopic rotifers, members of the protist kingdom, and much more.

His research, which began to circulate widely, opened the door to an entire world of microscopic life, making scientists aware of its existence.

Leeuwenhoek hired an illustrator to draw what he saw, allowing his writings to be accompanied by images, the descriptions of which remain recognizable today.

Leeuwenhoek’s Famous Magnifying Glasses

In his work as a merchant, Leeuwenhoek used magnifying glasses to analyze textiles, which is believed to have initially led him to learn glass polishing, a skill he mastered brilliantly.

The next step was to create his own magnifying glasses, which he then turned into powerful simple microscopes.

It is estimated that he built over 500 of them, using them for observations that originally began as a hobby.

One of Leeuwenhoek’s frequent subjects of study was himself. One day, he decided to look inside his mouth, analyzed his dental tartar, and discovered bacteria.

When he saw what he called “animalcules” moving, he thought:

They are living beings! I’ll see if I can kill them.

He then took boiling tea and observed that the heat indeed deactivated those tiny creatures.

He also removed the plaque from his mouth, sprinkled it with rainwater, and observed what happened.

To my surprise, it contains a great number of animals moving extravagantly. There are so many that their number exceeds the inhabitants of a kingdom.

British scientist Andrew Parker recounts that Leeuwenhoek even refrained from washing his feet for days or weeks to allow cultures to grow between his toes so he could observe them.

He also let lice live on his legs to study them.

British biologist Brian J. Ford notes that even shortly before his death in 1723, at nearly 91 years old, Leeuwenhoek “remained very busy.”

In the book Antony van Leeuwenhoek, Microscopist and Visionary Scientist, Ford comments:

He took notes on the samples (he collected) in the final days of his life. He spent time analyzing his own illness and the microscopic information he obtained through the dissection of the symptoms he experienced.

Leeuwenhoek Becomes a Celebrity

Leeuwenhoek’s biographers describe him as a man of great humility, despite the fame he acquired.

Kings and leaders from across Europe began visiting him to see his discoveries, his instruments, and his work.

Eventually, he had to set up a kind of exhibition with different microscopes or magnifying glasses, each displaying a sample, and people came to observe what scientists said he had discovered.

In 1716, Anton van Leeuwenhoek wrote:

My work, which I have been doing for a long time, was not aimed at gaining the praise I now enjoy, but primarily (to satisfy) a craving for knowledge, which I notice resides in me more than in other men. And, consequently, whenever I discovered something remarkable, I felt it my duty to put it on paper so that all ingenious people might also be informed of it.

Scientific Recognition and Legacy

For Leeuwenhoek, entering the scientific elite of his time was not easy. His biographers recount that convincing the experts of the Royal Society of London was challenging.

Telling the scientists, who were considered the sages of the time, that someone who was not a scientist had discovered something they did not know did not sit well with them. There was much reluctance.

He was even ridiculed by some of London’s brightest minds.

But after much research and even attempts to discredit him, in 1680, they had to acknowledge his achievements and named him a member of the organization.

Many of his observations, some dating back to 1673, were translated into Latin and English. But not everything was made public.

As J. Kremer recounts in The Significance of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek for the Early Development of Andrology:

It is somewhat peculiar but characteristic of the post-Leeuwenhoek era. His findings on sperm were kept secret. Between 1798 and 1807, The Select Works of A. van Leeuwenhoek were published, but all passages considered offensive to many readers were omitted.

It was not until the late 1950s that Leeuwenhoek’s research on sperm received the appreciation it deserved.

His legacy is extraordinary. He is the father of microbiology and optical microscopy. He was the pioneer of bacteriology, the man who saw “the invisible.”

That is the marvel of Leeuwenhoek, a person who stood outside the scientific world but whose ability to imagine and discover took him far—and with him, the rest of humanity.

No se encontraron productos.

We recommend

- What do we really know about the origin of IPA beers?

- 30 essential Belgian beers you should try at least once.