This post is also available in:

Español

Português

Tasting beer, in simple terms, means evaluating a food or beverage to examine its aromas, flavors, and quality. While most people naturally do this when consuming anything, it is not always done consciously.

Although there are nuances between beer tasting and beer appreciation, beer tasting is not strictly a professional exercise reserved for competitions. It is an activity that can be part of everyday life and, with study and practice, anyone can master it.

In short, everyone can learn to taste beer, identifying and appreciating its qualities and/or defects in detail, understanding what is right or wrong.

This is why there are no differences in tasting craft beer, homebrewed beer, or products from large breweries—the evaluation structure is always the same, based on the same objective parameters.

The quality of a beer is defined by the nature of its style and its organoleptic characteristics, not by who brews it.

This small reference guide compiles information to help beer enthusiasts understand the various aspects that can be considered in the global evaluation of a beer, detailing all its characteristics, their understanding, and application.

Contenido

Beer Tasting vs. Beer Appreciation

From a more specific perspective, there are differences between tasting and appreciating beer. Although these terms are synonymous, they serve different purposes in this context.

Beer appreciation is an activity that typically seeks the enjoyment of a product for hedonic purposes, requiring no prior preparation and based on subjective parameters.

Beer tasting, on the other hand, aims to develop a structured evaluation of a product through trained sensory analysis, continuous practice, and knowledge of processes, based on common guidelines and objectives.

Introduction to Beer Tasting

Beer tasting can be defined as the appreciation of the product through the use of the senses, focusing on five main aspects: aroma, appearance, flavor, mouthfeel, and overall impression. The goal is to perceive, identify, and appreciate the organoleptic qualities as objectively as possible.

It is not about indicating that a beer or some characteristic is simply “good” or “bad,” but about being able to use appropriate knowledge and language that allow a precise description that evaluates strengths and weaknesses.

Beer tasting can be classified into three types according to its specific objectives:

1. Educational Tasting

The main goal of educational beer tasting is to share knowledge, guided by a trained person, structured, and in an appropriate environment to promote learning about aromas/flavors, styles, and beer history.

2. Competition Tasting

Tasting beer in a competition is a structured evaluation process, conducted by trained and experienced judges, with the goal of identifying the qualities of a beer, its drinkability, and how appropriate it is to a specific style.

Additionally, it serves as a reference to detect problems and improve products. It is not only about identifying characteristics but recognizing their origin so that this allows correcting, adjusting, or improving the quality of a beer. Common references, evaluation sheets, and unidentified samples are used.

3. Quality Control Tasting

This involves tasting beer to use it as a tool for measuring consistency and quality control.

These are generally conducted by trained panels from the breweries themselves to evaluate that each production meets the defined standards for a specific product.

No se encontraron productos.

How to Organize a Beer Tasting

The most important thing in organizing a beer tasting is to have an adequate space and the essential material elements to carry it out.

1. Physical Space

Generally, it is required that when tasting beer, it takes place in a well-lit environment, with light colors, free of odors, and preferably at a room temperature close to 20°C.

It is recommended to place the samples on a white surface to allow adequate contrast in appreciation.

2. Equipment

A sufficient number of tasting glasses is required, preferably glass or tasting glasses.

Evaluation sheets, pencils, and a style guide for consultation and reference (BJCP or Brewers Association should be available.

3. Preparation and Order

Depending on the type of beer tasting, set up a separate area to avoid predispositions.

Generally, it is most recommended to order the service based on an increase in palate intensity and according to the recommended serving temperature.

4. Number of Samples

It is recommended not to exceed six samples per session, especially if they are high-alcohol and full-bodied products.

Provide purified water and pieces of neutral bread or salty crackers to cleanse the palate between samples.

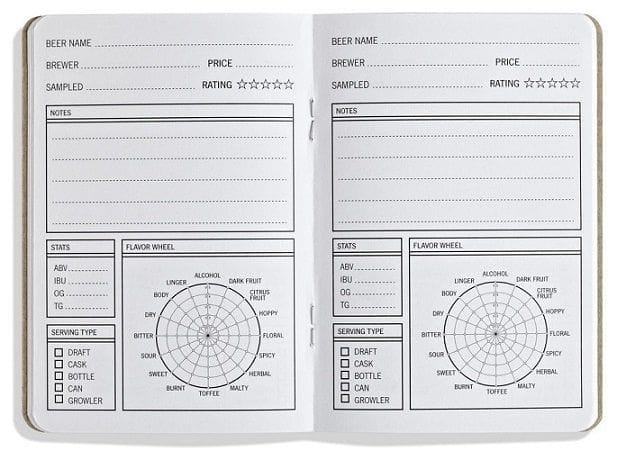

5. Tasting Sheet and Beer Evaluation

There are all kinds of beer evaluation sheets, whether for tasting or appreciating beer.

Generally, the preparation of this sheet has three basic objectives: to record the observed characteristics of the beer in a structured manner, to provide feedback to the brewer, and to compile a ranking of the participating beers.

Specific Considerations When Tasting Beer

The important thing here is to have prior knowledge of the beers to be tasted: type of beer according to fermentation (Ale, Lager, or Sour), specific style (Stout, IPA, Barley Wine, etc.), alcohol content (ABV), bitterness (IBU), and if it was made with additional ingredients (honey, fruits, etc.).

1. Beer Glassware

The glasses used when tasting beer should always be transparent, with smooth walls, without reliefs or decoration, very clean, drained upside down, and without water residue, ideally made of glass.

2. Serving Temperature

Regarding serving temperature, for each style, an appropriate range is recommended that will allow its best appreciation, but in general, the following ranges are established:

Beers between 4 and 6°C

Light Lager, Golden Ale, Cream Ale, Low-alcohol beers.

Beers between 6 and 8°C

Hefeweizen, Premium Lager, Pilsner, German Pilsner, Fruit Beer, Golden Ale, Berliner Weisse, Dark Lager, Fruit Lambics, and Gueuzes.

Beers between 8 and 10°C

American Pale Ale, Amber Ale, Dunkelweizen, Sweet/Dry Stout, Porter, Belgian Ale, Dunkel, Vienna, Schwarzbier, Altbier, and Trippel.

Beers between 10 and 12°C

Bitter, IPA, English Pale Ale, Saison, Unblended Lambic, Dubbel, Belgian Strong Ale, Weizenbock, Foreign Stout, and Scotch Ale.

Beers between 12 and 14°C

Barley Wine, Quadrupel, Imperial Stout, Imperial/Double IPA, Doppelbock, and Eisbock.

3. Tasting and Tasting Notes

Each beer style has its own balance of characteristics established by its history, ingredients, and brewing processes.

It is very important to be clear that the style does not define the quality of a beer, it only identifies the attributes we should expect from it.

At a higher level of interest, the proper understanding of these characteristics requires at least a basic understanding of the brewing process that allows recognizing how and where they originate, even how to adjust or correct them.

Basic Steps to Conduct a Beer Tasting

In general terms, the beer tasting process establishes a suggested sequence to approach the evaluation in the best possible way, from aromas to the overall impression, the sequence, quantities, and times that allow maximizing it.

An interesting article recommended by the BJCP and written by Eduard W. Wolfe describes the process of tasting beer in a series of recommended steps summarized below:

1. Inspect the Bottle Visually

Identify possible signs of problems (e.g., a ring around the neck that could indicate bacterial contamination or too much air space in the neck that could indicate possible oxidation).

These characteristics can be useful in describing the defects discovered when tasting beer, however, care must be taken not to prejudge.

2. Serve the Beer in a Clean Glass

Make an effort to produce a generous, but not excessive, head of foam. For highly carbonated beers, this may require carefully pouring the beer with the glass tilted.

On the other hand, for beers with low carbonation, this can be achieved by pouring from a height of about 15 centimeters from the bottle.

For each beer style, there is a time and way that will give it its optimal appearance.

3. Smell the Beer

As soon as you pour the beer, swirl the glass and bring it to your nose, inhaling several times.

When a beer is cold, it may be necessary to warm it slightly with the glass between your hands or cover the top so that the volatile aromas accumulate in sufficient concentration.

Take note of your impressions and, in particular, any aroma you can detect.

4. Visual Inspection

Tilt the glass and examine the beer against the light, taking note of what is observed.

5. Smell the Beer Again

Once again, swirl the glass if necessary and inhale the aroma of the beer repeatedly.

Notice how the beer’s aroma changes as it gains temperature and how the volatile aromas begin to dissipate. Take note again of all your impressions.

6. Taste the Beer

Take about 30 ml (1 ounce) and cover the entire inside of your mouth with it. Make sure the beer comes into contact with your lips, gums, teeth, palate, and entire tongue.

Swallow the beer, exhale through your nose, and take note of your impressions of the primary, secondary, and aftertaste flavors.

7. Taste the Beer Again

Take note this time about the physical sensations in the mouth that the beer produces.

8. Establish an Overall Impression

Relax. Take a deep breath. Smell and taste the beer again. Finally, pause to consider which general group to classify it in, for example, excellent, very good, good, drinkable, or with serious problems.

How to Taste Beer Like an Expert

The beer tasting process is based on an analysis that considers 5 aspects: aroma, appearance, flavor, mouthfeel, and overall impression, in that order.

If you want to taste beer to keep a record or convey this opinion to other people, even as a judge in a competition, the best way is to use a detailed procedure and common terminology.

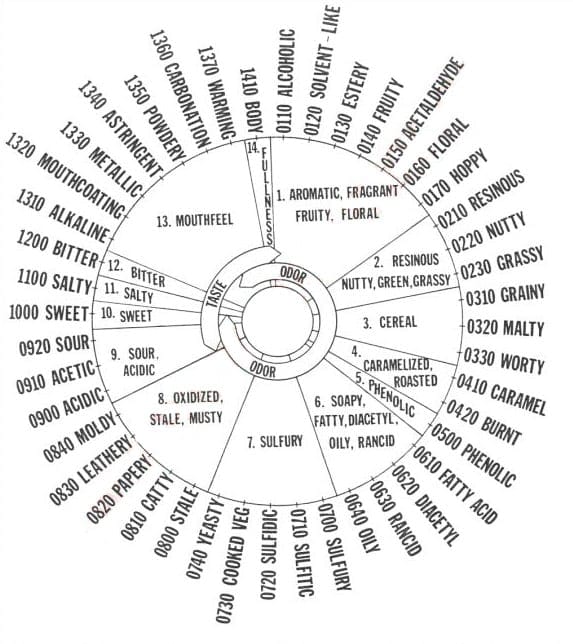

For this, one of the most used tools is the Meilgaard Flavor and Aroma Wheel.

1. Aromas

In this stage of beer tasting, the aromas of malt, hops, esters (fruits or roses), and other aromatic compounds are appreciated and described.

In beer, we can talk about primary and secondary aromas. The first contributed by the raw materials (malt and hops) and the second formed by the yeast during fermentation (esters, alcohol, spices).

In beer, there are aromas that are very volatile and dissipate quickly, so the first approach to the evaluation should be their detection and recording before they disappear or change.

In a BJCP-type competition, for example, the aroma evaluation corresponds to 24% of the total score (10 points).

Malt Aromas

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (sweet, grainy, toasted, smoky, caramel, nuts, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (bread, cookies, molasses, coffee, raisins, nuts, hazelnuts, etc.).

Malt aromas will depend on the types and quantities used according to the style brewed.

Hop Aromas

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (herbal, floral, resinous, earthy, fruity, citrus, perfumed, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (orange, grapefruit, passion fruit, pine, grass, roses, etc.).

Hop aromas depend on the variety and the amount added to the wort during boiling and also if added during fermentation or maturation. Generally, a beer uses several types of hops in its brewing.

Ester Aromas

These are aromatic compounds generally formed by the yeast during fermentation.

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (fruity, floral, solvent, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (banana, apple, lavender, rose, etc.).

Alcohol Aromas

Alcohol is the main byproduct of fermentation (along with CO2), so its presence or absence must always be mentioned.

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (not perceived, light, intense) and its character (spicy, wine-like, etc.).

Added Recipe Aromas

These are aromas originated by additional ingredients (fruits, vegetables, etc.). Mention if they are present and how well they integrate with the base beer style.

For example, the aromas of raspberry, cherries, and peach from Lambic beers with added fruits during maturation or coriander with orange peel added to Belgian wheat beers are typical.

Other Aromas

These are aromas related to characteristics developed due to inadequate brewing or distribution processes (fermentation, maturation, contamination, storage, etc.).

Observe if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (diacetyl, alcohol, oxidation, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (buttery, spicy, cardboard, etc.).

2. Appearance

In this stage, the beer’s color, clarity, and liveliness, the consistency, persistence, texture, and color of the foam are analyzed and described.

Although this set of characteristics has the lowest percentage estimation in the overall evaluation of a beer, in a BJCP competition, for example, it only corresponds to 6% of the score (3 points), many of them can function as indicators of the beer’s “health” and should be observed using a good light source and adequate contrast.

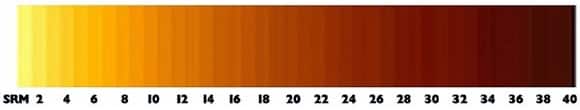

Color

Describe the beer’s color (white, yellow, reddish, brown, black, etc.) using some shade indicator (translucent, bright, matte, clear, cloudy, hazy, etc.).

The color range is associated with the style and does not represent the beer’s flavor, quality, or alcohol level and is mainly determined by the malt’s roasting level and in some cases by the addition of additional ingredients (fruits, vegetables, herbs).

The color intensity is defined by the SRM (Standard Reference Method) scale.

Liveliness

Visually quantify the release of CO2 dissolved in the beer by assigning a level (low, medium, bubbly).

The liveliness will be visible to a greater or lesser extent depending on the beer’s color.

Foam Consistency

Quantify the foam depth by assigning a size (low, medium, high, enormous) and describe its texture (light, dense, thick, compact, creamy, rocky).

Finally, observe and describe the bubble size on the surface (small, medium, large) and their distribution (homogeneous, heterogeneous).

Foam Color

Observe and describe the foam color (white, whitish, cinnamon, brown, etc.) indicating some degree of shade (translucent, bright, opaque).

These qualities are always related to the characteristic ingredients used in the brewing.

Foam Persistence

Observe the foam’s duration. As a reference, medium persistence is considered when the foam thickness decreases by half in one minute.

If the thickness decreases faster, the foam is considered not very persistent, if it takes longer, it is considered with good retention.

Finally, observe if it generates “legs” of alcohol (residue droplets) or foam rings (Belgian lace) on the glass walls.

3. Flavor

In this stage, the flavors of malt and hops, flavors developed by fermentation characteristics, the general balance between sweet and bitter, finish/aftertaste, and other characteristics are appreciated and described.

Although the flavor is mainly determined by the chemical reactions produced in the taste buds of the tongue, a very important part of its existence is determined by the sense of smell.

These characteristics are so important and complex that in a BJCP competition, they correspond to 40% of the overall beer evaluation (20 points).

When tasting beer, it should be sought that the beer comes into contact with the entire extension of the tongue and palate.

Finally, and contrary to what happens in wine tasting, the beer should be swallowed to evaluate in the areas of greatest sensitivity to bitterness, the finish, and the aftertaste.

Malt Flavors

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (sweet, toasted, caramel, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (black fruits, nuts, bread, grains, etc.). Confirm the olfactory sensations and/or record new ones.

Hop Flavors

Mention if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (citrus, resinous, earthy, herbal, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (grapefruit, passion fruit, peach, pine, grass, etc.).

Bitter Flavors

Mention if they are present, quantifying a level (absent, low, medium, high). In beer, bitterness mainly comes from hops originating from their Alpha Acid content, but it can be influenced by roasted malts and the type of water used according to the style.

The bitterness intensity is measured according to the IBU (International Bitterness Unit) scale. One IBU equals one milligram of iso-alpha-acids dissolved in one liter of beer.

Alcohol Flavors

As in the aroma, its presence should always be indicated. Mention if they are present (not perceived, light, intense) and its character (spicy, wine-like, etc.).

Other Aromas

Evaluate flavors related to characteristics developed due to inadequate brewing or distribution processes (fermentation, maturation, contamination, etc.).

Observe if they are present, quantifying the level (low, medium, high), the character (diacetyl, alcohol, oxidation, acidity, etc.), and any additional sensory indicator (buttery, spicy, vinegar, cardboard, etc.).

Balance

Evaluate the balance between the sweetness characteristics of the malt, the bitterness of the hops, and other flavor components according to the style (acidity, alcohol).

Quantify the balance by specifying a level for each component (balance towards malt, balance towards hops, imbalance, etc.).

Finish and Aftertaste

Mention the last characteristics perceived before the beer completely passes through the mouth (sweet, bitter, dry, attenuated, balanced, etc.).

The aftertaste is then the persistence of a flavor sensation after having passed through the mouth and being out of contact with the taste buds.

Mention and quantify its duration (absent, brief, lasting), intensity (soft, medium, intense), and character (malt, hops, toasted, etc.).

No se encontraron productos.

4. Mouthfeel

These are characteristics related to the physical sensations produced by the beer in the mouth: body, carbonation level, alcohol warmth, creaminess, astringency, and other palate sensations.

Generally, in a BJCP competition, these characteristics equate to 10% (5 points) of the overall evaluation.

Body

It is the sensation of fullness generated when the beer passes through the mouth (tongue, palate) caused by the dextrins and proteins of the malt.

Quantify by providing a weight (watery, light, medium, full) and describe its texture (silky, creamy, unctuous, chewy), indicating intermediate relationships if necessary.

Carbonation

Produced by the presence of CO2 dissolved in the beer. Natural carbonation occurs by adding sugar to the beer to reactivate the yeasts, and in artificial carbonation, CO2 is introduced under pressure.

Quantify by indicating a level (low, medium, high) and any descriptor if necessary (lifeless, flat, soft, sparkling, effervescent, etc.).

Alcohol

Mention any warm sensation related to alcohol and quantify using a level (low, medium, high) and any other sensation it might cause (burning, harshness, etc.).

Astringency

Often confused with bitterness or acidity, astringency produces a rough, contracting sensation on the tongue and palate and can develop both in the brewing process (milling, mashing) and from the ingredients used (roasted barley, hops).

Evaluate its presence and quantify using a level (absent, low, medium, high) and eventually indicate its origin (hops, malts, process).

5. Overall Impression

This is an opinion on the overall pleasure of having tasted a particular beer and is associated with all previous observations; it is the sum of objective and subjective sensations.

This final memory is a summary of the characteristics of each beer, highlighting what is most representative, and what will probably be remembered or commented on in the future.

In a BJCP competition, these characteristics equate to 20% of the overall evaluation.

Meilgaard Flavor and Aroma Wheel

In 1979, chemical engineer Morten Meilgaard developed a Beer Flavor and Aroma Wheel in an attempt to standardize an analysis language that would allow fluid communication between brewers, consumers, judges, writers, and anyone related to beer in any way, identifying and defining separately each identifiable aroma and flavor.

Subsequently, this work was jointly adopted as a standard by the European Brewery Convention (EBC), the American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC), and the Master Brewers Association of the Americas (MBAA).

Through this system, a descriptive name is given to each aroma and flavor to then group them with other similar aromas and flavors within 14 distinct classes.

The wheel contains a total of 44 first-level descriptors associated with common and recognizable terms by most people.

Then, a second level opens these first-level descriptors into 76 specific characteristics.

For example, under the class “01, Aromatic, Fragrant, Fruity, Floral” and under the descriptive name “0110, Alcoholic,” there are two associated descriptors “0111, Spicy” and “0112, Wine-like.”

Subjective terms like good/bad are not included. This is particularly important when judging in a competition since standardizing the descriptive language allows that when evaluating, not only is a beer described or rated, but it also allows establishing causes and characteristics associated with a range of possible recommendations that guide the brewer on what needs to be reinforced, corrected, and/or refocused in their recipe or process.

No se encontraron productos.

We recommend

- Charlie Papazian, the Father of American Craft Beer

- Opinion Column: Saison Dupont Beer – Tasting Notes