This post is also available in:

Español

Português

In the depths of what is now the Amazon rainforest, a scene from the dawn of time unfolds, featuring women from an indigenous Stone Age tribe.

Seated in a circle, they slowly chew cereal grains, transferring the enzyme ptialin from their saliva, which converts starches into fermentable sugars.

They then spit the resulting “mash” into clay pots. This marks the beginning of the ancient art of female beer brewing, a skill women likely mastered before the first bread was baked and certainly before the advent of wine.

For early humanity, beer was perhaps the most important staple in their diet—a valuable source of protein and vitamins, and a crucial milestone in ensuring our survival as a species.

Modern scholars suggest that the combined power of beer, both as a food and a mood-altering substance, might have given early humans the idea to settle down, abandoning their nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle forever.

Contenido

The Birth of Beer

Traditionally, historians place the birth of beer in the ancient lands of Babylon, Sumer, and Egypt.

However, some findings indicate that beer might have first been brewed in the Amazon basin around ten thousand years ago.

Certainly, the early civilizations of the Amazon had all the necessary elements to prepare the same styles that survive today among tribes in Brazil, Peru, and Ecuador.

Four thousand years before the birth of Christ, female brewers in Babylon and Sumer enjoyed great prestige, crafting dozens of types of beer.

Known as “Sabtiem,” Sumerian brewers had the distinction of being the only traders with their own deities.

Ninkasi—”the lady who fills the mouth”—and the goddess Siris oversaw the daily brewing ritual, which incorporated diverse ingredients like spices, peppers, tree bark, and powdered crab claws.

Women also distributed beer to breweries and taverns, and the price was always paid in raw grain, never in money.

The oldest legal code, the Code of Hammurabi, states:

If a beer seller does not receive barley as payment for beer, but instead receives money, or if the amount of beer brewed is less than the amount of barley received, they (the judges) shall throw her into the water.

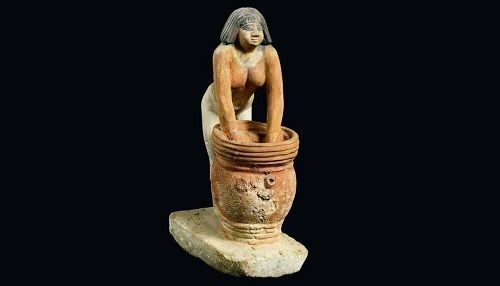

An additional gift to our world from these Sumerian women was the drinking straw. Ancient beer was fermented, grain husks and all, in narrow-necked, wide-bottomed clay pots.

During fermentation, impurities, husks, and grain residue floated to the top of the jar. The straw, usually made of beaten gold or silver, allowed the drinker to bypass the floating residue and enjoy the cleaner beer beneath.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

One of the oldest known tales, “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” references Siduri, an archetypal brewer who provided comfort and counsel to Gilgamesh, the greatest of Sumerian kings.

Archaeological sites across the Near East have yielded thousands of cuneiform tablets containing recipes and prayers in praise of beer.

Among the many types of beer brewed by ancient Sumerian women were: black beer, white beer, red beer, two-part beer, underworld beer, offering (sacrificial) beer, mother beer, dinner beer, horned beer, wheat beer, and beer with a head.

Like in later ancient Egyptian society, Sumerian-Mesopotamian beers were brewed from bread loaves called “bappir.”

Barley malt was first prepared as a bread cake, which was then crumbled into water and, with the help of airborne yeast, underwent fermentation.

Beer in Egypt

For the ancient Egyptians, beer was so important that the hieroglyphic symbol for food was a beer jar and a bread cake.

Egyptian hieroglyphs speak of dozens of beer varieties, both for this world and the next.

Pharaohs were routinely buried with small but complete breweries and small wooden brewers to ensure a regular supply of beer on their arduous journey to the afterlife.

One Egyptian beer, called “Hekt,” was widely exported to the known world, reaching as far as Rome, Palestine, and even India.

Egyptian women brewed their beer in a kitchen area called “the purity,” and the lady of the house always oversaw its production.

Although royal brewers were sometimes men, most Egyptian beer was brewed and sold by women who developed dozens of beer styles: brown beer, iron beer, sweet beer, strong beer, white beer, black beer, and red beer, among others.

Special religious beers included “friendship” beer, “protection” beer, age beer, truth beer, the beer of the goddess Maat, and “Setcherit,” a narcotic beer used as a sleeping aid.

Hops were unknown to the ancient Egyptians, though other bitter herbs like lupin and sium sisarum were used in brewing or served as appetizers alongside the beer itself.

The Greeks, despite importing shiploads of Egyptian beer, never fully trusted it.

The Greek physician Dioscorides complained that Egyptian beer, called Zythos by the Greeks, made them urinate too frequently.

Other Greek physicians even believed beer was the direct cause of leprosy. Despite these suspicions, Greek artisans used beer to soften ivory in jewelry making.

In the Egypt of the pharaohs, beer was the sustenance of life: slaves and commoners, soldiers and kings, women and children—all drank beer.

In fact, the minimum wage was two containers of beer per workday, making beer the most basic element of exchange.

The barley bread brew also played a significant role in the religious life of the Egyptians. Consider the ancient myth explaining the birth of beer:

The Sun God Ra, having lost divine patience with the increasingly wicked human race, decided to punish them for their sins, entrusting the task to the goddess Hathor. She performed her task so efficiently that the streets were “flooded with blood,” nearly wiping out humanity.

But once Hathor began her work, she was not easily stopped. To halt her, Ra took the human blood flooding the cities, added barley and fruits, and the resulting mixture became the world’s first beer.

The next morning, when Hathor returned to finish her task, she was stopped by an ocean of beer, which she quickly drank, becoming drunk, forgetting her mission, and falling into a deep sleep.

Thus, Hathor became the Egyptians’ primary goddess of beer and drunkenness.

However, the abuse of beer, this gift of the gods, was frowned upon by the ancient Egyptian middle class.

In the Sallier Papyrus, a father tells his son:

I have been told that you neglect your studies, desire joy, and go from tavern to tavern. He who smells of beer repulses and keeps people at a distance, hardening their souls. You think it fitting to run against a wall and knock it down; people will flee from you. Do not give beer a place in your heart; forget the dregs. Do not start drinking. If you speak, nonsense will come from your mouth, and your companions will rise and say, ‘Away with the drunkards’.

Another temperance advice comes from what is perhaps the earliest known description of death from alcoholism, taken from a tomb inscription around 2800 BC:

His earthly dwelling (body) was spoiled and broken by beer; his spirit escaped before it was called by God.

Despite its abusive consumption, beer remained a primary component of all ancient Egyptian medicine and seems to have been very beneficial to the people of the Nile Valley.

Beer and the Vikings

For nearly two centuries, the Vikings sowed terror across the civilized world. In a state of beer-induced madness, they raped, burned, and plundered their way through North Africa, the Netherlands, England, Ireland, Wales, France, Germany, and Italy.

This Viking brew was called AUL, a term that corresponds to the English root of the word ALE, a beer style that spread as the Normans conquered new lands.

Viking women were the exclusive brewers of Norse society, and the law dictated that all equipment in the brewing room was their exclusive property.

As for the creation of beer, Norse myth offered the following explanation: The gods were at war with a human tribe called the Vans, and only after much slaughter was a peace conference arranged. The treaty was sealed by members of both sides spitting into a jar.

To preserve the occasion, the gods took some dust and transformed the saliva into a man they named Kvaser.

Kvaser was soon killed by a race of dwarves, who collected his blood in an iron kettle. The dwarves then added honey to the mixture, and the result became beer.

The Norse paradise, called Valhalla, was nothing less than a giant brewery with 540 doors, where the Viking god Woden entertained the dead with tales of battles and jars of beer.

This beer was provided from the udders of a mythical goat named Heidrun, whose infinite generosity of beer kept the divine enterprise in a constant state of bliss.

On Earth, Viking women drank beer, jar by jar, alongside men. In a trance-like state, the “bragg” women predicted the future under the influence of the beer they brewed themselves.

This “bragging” played a vital role in their religious life, as did the “runes,” magical inscriptions placed on beer jars to ward off evil.

The Finnish Kalevala

The ancient Finnish people credit the birth of beer to the efforts of three women preparing for a wedding feast.

Osmotar, Kapo, and Kalevatar worked together to brew the world’s first beer, but their efforts were in vain.

Only when Kalevatar combined bear saliva with wild honey did they achieve the coveted beer foam, and this gift made its way to the world of men.

From the Kalevala, the ancient Finnish story of the world’s creation, we can see the importance of beer in human society.

In this early origin story, the creation of beer occupies twice the narrative space dedicated to the creation of the world:

Great, indeed, is the reputation of ancient beer.

It is said to make the weak strong,

famous for drying women’s tears,

famous for cheering the broken-hearted,

making the timid brave and powerful,

filling the heart with joy and gladness,

filling the mind with wisdom,

filling the tongue with ancient legends,

only making the fool more foolish.

No se encontraron productos.

England and the Middle Ages

Even in the 13th century, records from an English town show that less than 8% of brewers were men.

Beer remained an essential part of the diet, and the sale of surplus beer became a significant contribution to most households’ economies.

When a housewife had extra beer to sell, a long stick was placed over the front door or on the road, sometimes adorned with a hop garland. This custom can be found in one form or another in all primitive societies.

African natives signaled the availability of fresh homemade beer by displaying a garland of vines and fresh flowers outside the hut of the woman who brewed it.

How this universal symbol became synonymous with “beer for sale” is a mystery of the human collective unconscious.

With the advent of public taverns, women remained as brewers in medieval Europe, but unless they were widows, they could only hold a license in their husband’s name.

The penalty for selling spoiled or adulterated beer was flogging. However, the husband could retain the license if he used the whip on his wife.

As beer was considered a vital food, good beer and honest measure were expected from wives, and dishonesty was not tolerated.

A wood carving of a brewer woman being dragged to hell by several demons still resides in a church in Ludlow, England.

The condemned woman holds in her hands the double-bottomed beer jar she used to cheat her customers.

Another figure from the early church was Saint Brigid, who, through an act of prayer and faith, changed the water of a bath into beer for a colony of thirsty lepers.

Beer in the New World Colonies

In the New World colonies in America, women continued to brew beer for their families and neighbors.

The early settlers of the United States drank large quantities of beer as a nutritious respite from a diet of fish and dried, salted, and smoked meat.

Ingenious women brewed beer with corn, pumpkins, artichokes, oats, wheat, honey, and molasses. Even before a wedding, a bridal beer was brewed and sold, with the proceeds going to the bride on her wedding day.

Sadly, by the late 18th century, the decline of homebrewing as a domestic art began, and the development of beer as a male-dominated business took off.

Alongside large-scale commercial brewing, the number of beer styles available to the public began to decline.

Unusual and regional beer varieties developed by women over centuries of trial and error became endangered and eventually disappeared.

We recommend

- Esters vs. Phenols in Beer: What’s the Difference?

- Digital Media and the Environmental Impact of Print Media